by Dave Arnold

Nils and I recently visited the great state of Kentucky, home to some of the finest country ham producers in the world – including Finchville Farms.

While visiting Finchville it dawned on me that I’ve never posted on country ham. The shame! Before I was known for tech many people knew me as that guy who loves country ham. I’ve always loved it; I have fond memories of my grandma serving it to me with her red-eye gravy. I became a certifiable country ham nut in 2004, while trying to start The Museum of Food and Drink (I’m still trying to get that off the ground.) I was researching country ham for an exhibit, with the goal of spreading my belief that American Country Ham is a national culinary treasure that can be appreciated in a very modern way by eating it uncooked and sliced thin on a meat slicer –the same way we enjoy prosciutto.

My brochure from the exhibit, including a list of producers and tasting notes, can be downloaded here, and at the end of this post I reprint the exhibit text. In 2007 I wrote an article on dry cured hams for Food Arts magazine, which you can read here.

Some of my current country ham thoughts:

1. American country hams are often difficult to slice on a meat slicer because the cushion –the meaty part of the ham — is usually a bit wet even when the outside of the ham is quite dry. This wetness is the result of most country hams’ shape, which prevent uniform drying. Country ham producers don’t mind the wetness –in fact they like it, because they intend to cook the ham. But this wetness presents obstacles to those of us who want to eat the ham uncooked. I’d like to experiment by rubbing the outside of some hams with a lard/flour mixture — I think I could do some long aging (two years or more) without overly drying the outer portions.

2. I believe the characteristic flavor of American ham comes from our high aging temperatures and humidity –usually far higher than European hams. I think the high temperatures bring on that country ham funk I love so much. I’d like to see some of the chefs who are curing their own hams make an American-style product — most are working within the European lower temp, lower humidity parameters.

3. Country hams are salty –stop whining. Don’t overcook them and they won’t seem so salty –better yet, don’t cook them at all.

4. Today some high profile chefs are working to popularize American country hams, and I’m thankful for it.

OK, now the exhibit text:

AMERICAN COUNTRY HAM | From The Museum of Food and Drink Exhibit November 2004

If you were raised in America, you probably think of ham the way it’s traditionally found in grocery stores today—pumped full of water and ready to be dressed in its holiday best, cooked with sugar syrup and pineapples. Introduced in the 20th century, these “city hams” don’t have much depth of flavor but are cheap to produce and are by far the most popular hams in this country. But American artisanal ham producers have been producing an entirely different, superior product for the past four centuries: ham that is dry-cured and aged, called “country ham.”

City Ham, Country Ham:

There are reasons you don’t find dry-cured American country ham at your grocery store deli.

- Producers must invest four months to a year aging a country ham, taking up space and tying up capital. They don’t see a return on their investment until the ham is ready for retail.

- The older and better a ham gets, the more it shrinks due to lost water. Some hams in this show have lost more than 30 percent of their original weight; they must lose a minimum of 18 percent by law to qualify as country ham. The cost per pound at retail, therefore, is much higher than a city ham.

- The old saying goes: Forever is two people and a Virginia ham. From a taste and cost perspective, we should buy whole country hams and eat them gradually in small, thin slices. But most modern consumers don’t want a whole leg of a pig occupying their fridge for weeks, nor are they comfortable carving it. Producers have tried to address these inconveniences by offering packaged “center cuts,” which are essentially ham steaks. The problem: They are usually too thick to show off a cured ham to its best advantage.

Long ago, meat packers figured out a way to solve all three of these problems at once with the “city ham.” City hams are pumped full of a brine mixture—usually water, salt, sugar, nitrates and other chemicals. The brine is often pumped directly into the pig’s femoral artery so that it circulates throughout the ham (industry lore is that an embalmer came up with this method). The process reduces the cure time to almost nothing, giving the meat a cured flavor and color in a fraction of the time of dry aging. The brine also makes the ham sweet, mild and semi-salty, so it can be carved into thick slabs and eaten with a fork and steak knife. And unlike a cured and aged ham, which loses weight over time, the brine-cured city ham often weighs more than it did before brining when it’s sold, adding up to higher profits for the producer. As Americans have adopted this as their de-facto ham, dry-curing has become a dying art in the American South.

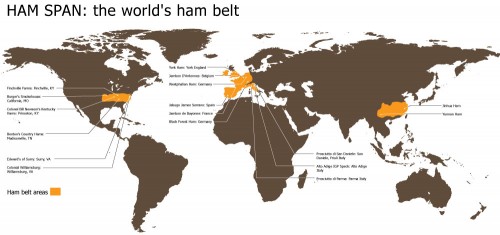

Ham span: Climate and the world’s ham belt:

Curing hams was a matter of necessity in the days before producers could rely on commercial refrigeration. When cold weather arrived, farmers (most of whom kept pigs) had to choose between slaughtering their pigs and feeding them through the lean winter months. Often they decided to slaughter them. American farmers living in areas like Virginia, Tennessee, Kentucky and North Carolina, where winter temperatures hover between 32 and 42 degrees, were in luck: They could dry-cure their slaughtered pigs during the winter without risk of spoilage or freezing. In states farther south, like Florida, the pork would spoil in warm temperatures; in the north, hams would freeze, preventing the cure from penetrating the meat. During the springtime, mild weather in the good ham-curing states gave the hams time to equalize their salt content and begin drying out. The hot, fairly humid summers in the American South are likewise perfect for the next stage in the process: Higher temperatures activate enzymes that break down proteins and fats in the meat, giving the finished product a distinct aged flavor. This process is referred to as “the sweat.” Heat = aging = flavor. And humidity keeps the ham from getting too dry. So while Virginia has always been a state for ham lovers, Arizona is not: A Phoenix summer would produce a crop of dry, oversized paperweights.

Cold –but not freezing— winter weather was the first thing our ancestors needed to make a great dry-cured ham. If the climate was too cold, a whole ham would freeze before it could be cured in the classic technique. If too warm, a whole ham would spoil. The tradition of the dry-cured ham, therefore, wraps around the world in a distinct climate zone. This ham belt includes most of lower Europe and the Mediterranean, is interrupted by Islamic interdictions on pork consumption, extremely high mountains, and vegetarian based cultures, and picks up again in China (from my Food Arts article. click on image to make it bigger).

Of course today we can create ideal ham-curing conditions almost anywhere, with a period of artificial refrigeration followed by a period of heat and humidity. Some good ham, for instance, is now made in Canada. But the culture of great ham started—and lives on—in the world’s ham belt, which runs through the southeastern United States, southern and central Europe, and southern China. To this day, artisans in those regions are making hams in ambient conditions with no artificial temperature controls. As a result, their hams are distinct to a year and region, much like wine.

Raw feed: Is country ham safe to eat uncooked?

Yes. USDA-approved country hams have been cured and are safe to eat without further cooking. The producer decides whether to label the ham RTE (ready-to-eat) or NRTE (not-ready-to-eat). If a ham is labeled NRTE, USDA law requires the producer to including cooking instructions on the ham, advising the consumer to essentially cook all the juices out of the meat until it turns into a salt-encrusted piece of shoe leather. Most producers opt to label hams NRTE, partly to avoid the scrutiny of inspectors but also because the custom in this country is to cook hams anyway. This practice is unfortunate: American cured hams are safe to eat uncooked, like prosciutto or other cured meats, and typically taste better that way.

Now we’re cookin’:

Americans typically eat their country hams cooked (overcooked, in fact –turning them into salt licks), just as we’ve traditionally prepared the more common brined city hams. We inherited this practice from the British. The famous country hams of Bayonne, France and Westphalia, Germany are now eaten exclusively cured but were traditionally eaten both cooked and uncooked. Italian prosciutto and Spanish Serrano hams have always been eaten uncooked. As you’ll see in the uncooked American hams offered for tasting, country hams need not be cooked to be delicious.

Proud to be an American

Countries in the ham belt have distinct methods of curing and serving ham. Just as you wouldn’t call a California pinot noir a Burgundy (even though it’s made from the same grape), you shouldn’t call our regional cured hams “American prosciutto” or “American Serrano” when they’re served uncooked. Hams from Virginia, Kentucky and other states hold their own against Italian and Spanish hams and should be referred to by their proper designation: artisanal country hams. Confusing the names does both parties a disservice.

This little piggy

Most hams come from pigs that were bred for commercial use and raised in factories. Factory pigs gain weight quickly, bear many offspring, and, to suit today’s consumer, have large amount of lean meat and very little fat. Lean meat wasn’t always a priority, however. Until the rise of vegetable oils and shortening, lard was one of the most important pig products, and pigs were raised to be as fat as possible. America’s fat paranoia has made fatty pork less popular, which is good news for the modern pork industry: Lean meat requires just a quarter of the calories to produce than fat does. The new leaner pigs therefore take much less time and money to feed: a mere 2 1/3 pounds of feed provides a pound of weight gain for a pig, most of it very lean. Of course, super-lean pork does not make a great ham. A dry-cured ham without fat feels rough in the mouth, is overly salty and doesn’t have the characteristic texture of an old-fashioned country ham. Some big pork producers have started putting a little more fat back into their pork, and we can only hope that others will follow.

Large-scale pig farmers choose specific breeds for their growth, reproductive, and lean-meat traits, but some smaller scale farmers who are more concerned with the end product prefer breeds that produce great-textured and flavorful pork. Among major commercial breeds, Durocs have the most intra-muscular fat and make great hams.

Some older-heritage breed pigs with great fatty meat such as Berkshire could be produced on a larger scale, if consumers started demanding this type of pork. But other great tasting ones such as Tamworth (a friendly pasture pig and great forager) and Ossabaw (extremely rare, extremely fatty pigs originally brought to America by the Conquistadors) simply don’t translate to mass production for specific reasons. The Tamworth, for instance, doesn’t built up muscles—and therefore doesn’t bulk up quickly enough for larger-scale farmers. And the Ossabaw is small, too fatty, and mean as hell, so it’s hard to handle.

They are what they eat

Prior to the rise of large-scale industrial farming, pigs were usually fed scraps and byproducts from the farm. Pigs are voracious omnivores and will fatten themselves with almost anything you throw in front of them. Throughout history they’ve proven to be thrifty animals on a farm, because they essentially turn waste and garbage into tasty meat. Of course the flavor of that meat has always been determined by a pig’s particular location and diet. Brewers would feed their pigs spent barley mash (this doesn’t produce good pork). Dairy farmers in northern Italy would feed pigs leftover whey from cheese manufacturing, which produced incredibly tasty meat; this is still considered an ideal diet for pigs that will become prosciutto. In Virginia, pigs traditionally fed on leftover peanuts and peanut greens in the past. Nuts and oily legumes build up good intra-muscular fat, and that particular type of fat is more liquid, resulting in a silky final product. Peanuts are no longer a waste crop, however, so they are no longer part of the pig’s diet. Perhaps the happiest pigs were those who lived on farms near the forest, because they were allowed to forage the woods for hickory nuts and acorns. This feeding style is called mast feeding, and it produces fantastic ham with similar properties to the peanut eaters. Very few pigs are raised this way commercially today, and what was a thrifty practice in the past has become an incredible luxury. The famed Iberico ham from Spain, raised on acorns, fetches a fantastic price and is not yet imported into this country (Note: it is imported now).

The fresh ham

When choosing a fresh ham to cure, producers select their size, then decide how they want the fat trimmed and how long they want the shank cut. Most American producers begin the curing process with hams that weigh in between 20 and 23 pounds. Smaller hams would dry out too quickly, and larger hams could spoil before the cure penetrates the meat. Some Spanish producers of larger Serrano style hams, however, lean toward gigantic hams, which, if cured correctly, have a few advantages: They come from larger, fatter pigs, which have more aging potential and more flavor. The fat ameliorates the saltiness and dryness of the meat, and the hams dry out less over the two-or- more-year aging process used in Spain. A two-year-old American ham tastes great but is drier and saltier tasting than a larger Spanish ham would be. Shank length is also a matter of preference. The Italians and the Spanish prefer a very long shank, sometimes including the hoof; the Spanish Iberico “pata negra” comes with a black hoof, a sign of its pedigree. Some producers contend that hams spoil around the shank and therefore request short shanks. Ham producers must also consider how the fat is trimmed. Prosciutto makers leave all the skin on the ham to protect it from over-drying. Some Spanish even out the drying of the ham by cutting the skin off in an easily identifiable V shape. Americans typically cut off a collar of skin around the butt end of the ham.

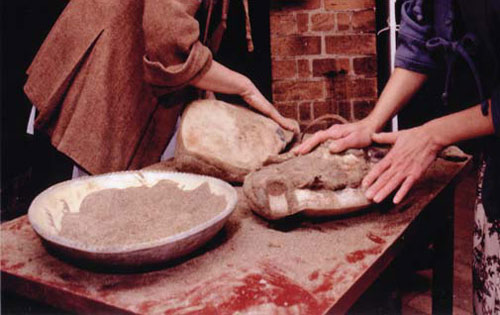

Cure genius

Every year the staff at Colonial Williamsburg salts down some hams in the really old school way --using 18th century implements. Modern production isn't much different.

The curing process begins by rubbing the fresh ham with salt and sometimes sugar, spices and nitrates. Italian prosciutto and Spanish Serrano hams are made with a pure salt cure and no added nitrates or nitrites. Some American hams are also nitrate free. When used, nitrates ensure a pink color and cured flavor in a short amount of time, and provide some anti-microbial benefits as well. Nitrates are not a modern addition to the curing process; they have been added to hams in the form of saltpeter for hundreds of years and in the form of impure salts for millennia. Meat naturally contains a small amount of nitrates, however, which allow it to take on a beautiful color on its own. The longer a ham is aged, the fewer added nitrates are necessary. Many American hams are cured with brown or white sugar in addition to salt. The sugar is not for sweetness, but rather serves to soften the harshness of the salt and the toughening effects of nitrates. Red and black pepper is sometimes added as well, lending some flavor but also discouraging bugs from attacking the ham. Machines are typically used to rub the cure into factory-produced ham, but as any ham artisan will tell you, the hand of the skilled salter is important. All of the American hams at the exhibit are hand salted.

Ham’s off!

After finishing the cure, many producers still use traditional methods to protect their hams against pesky bugs like red-legged ham beetles and cheese skippers. Some producers cure each ham in its own bag, using only the amount of cure necessary, and then leave the ham in the bag for protection. Others bag their hams after the cure. Some coat the outside of the ham with spices like black or red pepper to deter bugs. Long ago, some hams were dipped in hickory ash as anti-bug insurance. Prosciutto is rubbed with a lard mixture for the same reason, and also to slow the drying process.

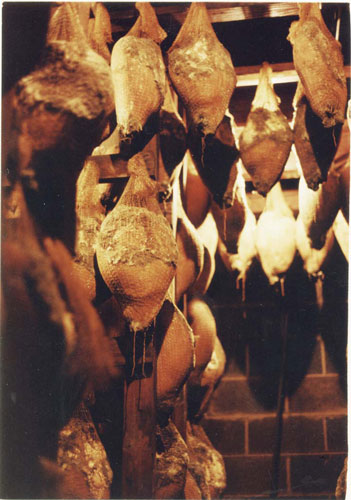

How’s it hanging?

How to hang the ham: hock up or hock down? It’s not as silly a question as you might think. Hanging hock up, as you see in most stores, causes the ham to assume a narrow bullet shape. This helps hams dry out evenly, which the Europeans like. Most Americans hang their hams hock down, because it pulls the ham into a squatter “ham” shape and leads to moister ham, which suits the American palate.

Smoke them if you’ve got them

We usually associate the smoking process with flavor, but in the past—both in America and in Europe—smoking provided an extra layer of food safety: It helped kill bacteria. Smoking in Europe depends mainly on geography. In the southern sections of the ham belt, such as Spain and most of Italy, producers have left their hams un-smoked, while those in Alpine Italy, Germany, the UK and Belgium have smoked their hams. In the United States, Tidewater Virginia is known for heavy smoking and North Carolina is known for little or no smoking, but everywhere else it’s the producer’s preference and not the location that determines the use of smoke. Farmers just miles from each other might use entirely different techniques of curing and/or smoking. Those who do smoke their hams in the U.S. tend to use hickory or oak; Europeans also use hardwoods but sometimes add aromatics such as juniper.

Age before beauty

Producing a perfect ham is a balancing act. While aging develops and concentrates a ham’s rich flavor, it also reduces the ham’s moisture and accentuates its saltiness. Fat inside the ham helps counteract these effects, and is therefore a key part of aging. A ham with generous amounts of fat can be aged longer for more intense flavor, without drying out. The local flora of a region helps determine the flavor of a ham. Micro-ecosystems are so important that some producers say they can taste and smell the difference in hams that are from two different aging rooms at the same facility. During aging, molds grow on the outside of hams (molds that are specific to the ham house). The mold-covered hams don’t look all that pretty on the outside, but the mold, much like the type that grows on a rind of a cheese, helps develop special flavors in the meat. Enzymes inside meat, which are partially dependent on good bacteria and molds in the ham house, break down the protein and fat in the meat over time to give ham its characteristic flavor. This prime of this process is in the summer, when temperature and humidity is high. A two-year old ham does not benefit from two full years of aging per se, but rather from two full summers of aging, with some time in between.

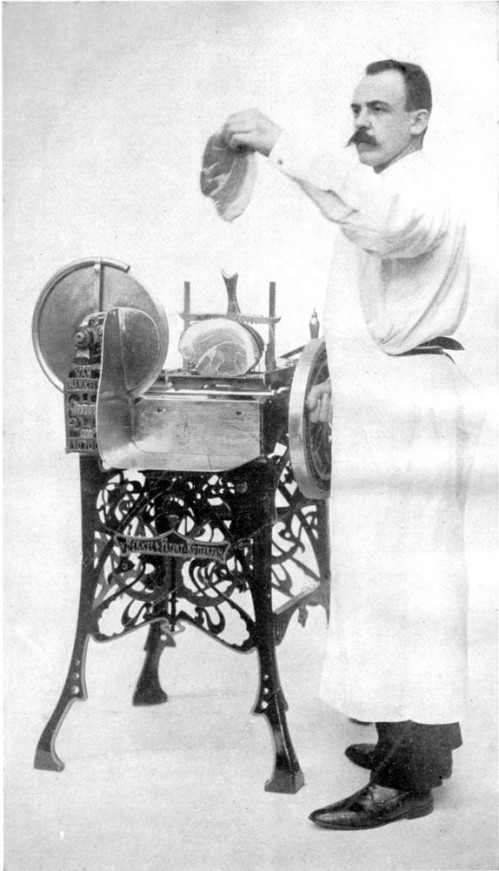

The Slice is Right

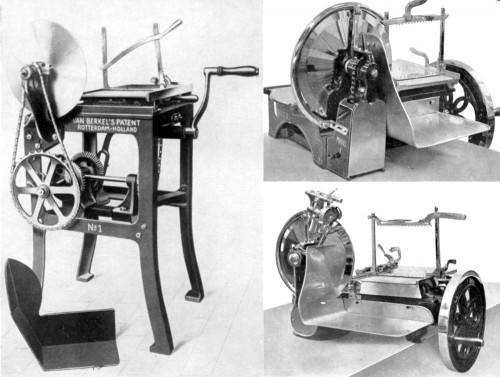

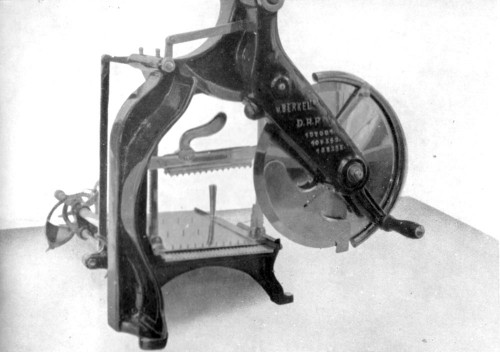

W. A. Van Berkel patented the first commercial meat slicer in 1898, ushering in an era of modern slicing and eventually eliminating the need for highly skilled slicing personnel at butcher shops and delis. In the days before this technology, prosciutto and serrano ham was left on the bone and painstakingly sliced into strips, parallel with the muscle fibers. Many Spanish butchers have maintained this slicing tradition, however in the US the vast majority of these European hams are now boned out and machine sliced paper-thin across the grain. Ham aficionados still insist on slicing meat the old way, parallel to the grain, claiming that slicing this way increases the chewiness (some might say toughness) as well as the perception of flavor. They also claim that machine slicers, especially fast-spinning modern ones, melt the fat of the slices, thereby ruining the mouth-feel of the ham. This is debatable—but the advantages of machine slicing are not. Slicing a boned ham on a machine reduces waste and produces a uniform, extremely tender slice. And we can thank Berkel for the proliferation of prosciutto-style ham: The emergence of machine slicing has brought thinly sliced cured ham to people around the world, and to many who would never have gone to the trouble of tasting hams that needed to be hand sliced by a trained carver.

A very hamusing article. Primo.

This just made my nipples hard.

Cooking westfalian ham? Why would you do that?

Most German hams are either smoked (and not cooked afterwards, with the exception of bones in split pea soup) or resemble your city ham. There is also Kassler, something the Brits would call gammon and Burgunderschinken (German burgundry ham, which is indeed oven baked or roasted on a spit.)

But cured, cold smoked German ham is typically sliced and eaten as is.

Yo Dave,

I dunnno if you never posted on country ham before, it feels like i read some stuff bout it (from you) some time ago…

On thing that occured to me is that uncooked ham can have some dangers like trichinosis can´t it?

In Germany (most Europe) every single Pig that is slaugtered is analyzed for tirchines. This used to be done by a special health officer looking at parts of the pig to identify the small worms in a microscope. This was done on every single pig! The guy was called pierekieker (flat German for worm searcher).

Nowadays it is an antibody test on the trichina. You can pool many pigs and test them. If negative fine. If positive, test all pig individually. Occurrence rate in Germany very low…

Anyways, 20 year ago I read an American travel guide for Germany, and laughed my head off: it warned from eating the famous German food called “mett”, minced raw pork on a good roll of bread. This might be deadly in the US but totally safe in Germany! Unless you buy it at a sleazy place where it is prepared in the morning and eaten 8 hrs later after storage at room temp. (This is dangerous with any meat.) Buy your meat fresh at a butcher and enjoy!

So after this Schinderhanneseske long intro my question:

Ain´t trichinosis a danger with country ham from untested animals?

Just curious. I´d be willing to take the risk any time…..

Howdy Schinderhannes,

Luckily, country ham is totally safe. The combination of high salt and low water activity guarantees trichinella death. As a second defense, trichinosis infection in pork is extremely rare in the US today.

Hi Dave.

Great ham post. I haven’t posted much recently because I just got married and returned from my honeymoon. Guess where I went…?

SPAIN! This post brought back some nice recent memories (and made me very hungry for) some iberico, serrano, lomo, and chorizo.

What would you recommend as an outstanding country ham that is RTE? I would like to pick one up and possibly compare to the lomo and chorizo i have at the house still vac-sealed and screaming my name.

Howdy Jason,

All the real country hams are safe RTE (ready to eat products) if they are cured properly. The trick with country hams is finding the good ones. Most aren’t cured using the best techniques and some manufacturers make high end and lower end products. Most people are cooking the hell out of the hams and as a result can’t tell the difference anyways. You should always speak to the producers over the phone to figure out how old your particular ham is. Don’t go less than 9 months or so or the ham will be impossible to slice. In Va try S. Wallace Edwards country ham. Ask for the Wigwam ham and ask how old they are. In Tn look for Benton’s (again, ask how old). In Ky look for Colonel Newsom’s or Finchville farms (plus a couple others –don’t forget to ask how old). In Mo, look for Burger’s, but remember they are a big operation and they make many commodity hams in addition to their traditional ham –which they call attic aged. The tasting notes for these hams are in the downloadable pdf at the beginning of the post. Of those people I mentioned, I am most familiar with Colonel Newsom’s (run by Nancy Mahaffey), Edwards (run by Sam Edwards), and Finchville Farms. They all make excellent products.

What hams would you recommend in Canada?

Hmm, I think all the southern folks will ship to Canada. I don’t know any old school producers up there cause it is a bit far north (which doesn’t mean a great product can’t be made now).

Ok, thanks

An alternative is to do your own ham – quite easy, actually. I’m sure you have not far from your place some organic pig farm where you can easily get a pig leg, with very good meat quality. Give it a try, it is worth it!!

Have you made your own dry-cured ham? At my home we are in the middle of this process, and I’m nervous that I may be using too much salt.

About a week ago we drove out to the farm and came back with two whole lambs and a whole hog. We are not trained butchers, and although my husband thought he had removed the “aitch” bone (basically the acetabulum part of the pelvis) when I went to turn over the two hams I discovered he had not.

I got out the boning knife and removed at least a pound of meat from each ham along with the pelvis remnant. I now had the ball of the femur visible on both hams, as per the instructions we were working from. Of course, I’d also removed most of the salted cut meat surface, so I resalted.

We’ve got both hams in a large cooler, lying skin side down, stacked, with a metal rack underneath to keep them out of the liquid that drains. I am pulling them out every other day, pouring out the reddish liquid/salt glop and I’ve been applying more salt to any spot that looks wet to me, with special attention to the bone, since that seems like the biggest risk for spoilage.

I’m an MD and my greatest concern has been avoiding spoilage, but now I’m worried that I may have over-salted these hams. My plan is to have them in the cooler with salt for three weeks, then they start hanging in our basement. I was going off instructions for prosciutto, so I was planning on coating the cut surface with lard et al.

I haven’t made my own. As you probably know, salt absorption can be calculated two ways: number of days and exact amount of salt per unit weight ham. Obviously the latter is the most precise, but most producers use the former. A good reference is Virginia Tech’s pdf http://www.uga.edu/nchfp/how/cure_smoke/virginia_ham.pdf. Please tell us your results.

Just returned from Kentucky, myself. The trip was primarily about bourbon & horses, but we managed to make some time for ham. The “Father’s Country Ham” from Gatton Farms off the charcuterie menu at 732 Social in Louisville was particularly fine.

I love making my own sausage and have cured bacon at home, but this article REALLY piqued my interest. I live in Northern CA and heard it’s one of the Mediterranean-climate zones amenable to the bacteria that acts in Italian/Spanish cured meats and sausages.

Your quantity/storage comments seem to indicate you need to refridgerate following cutting into the fully cured ham, but is there a way around this?

My mouth is watering just reading through this document. Many thanks!

Old timers wouldn’t refrigerate after cutting (cause they had no refrigerators). One old-timer told me his family would just rub some lard on the cut face and keep on hanging the ham. Theoretically, some staph bacteria could survive on the cut face of a country ham, but I don’t know for how long –especially if exposed to the air and allowed to dry even a little bit.

Nothing beats a Smithfield Ham from Virginny! Nuttin’!

Next time you’re in San Francisco:

http://www.hogandrocks.com/

Will do.

On trichinosis, I thought that it had been practically eliminated in US pigs?

On lean ham, I was in southern india a little while ago (kerala in fact), and the “porka” that I had there seemed to allways have thick, delicious layers of fat on it. Totally different from any pork I’ve had in the US, its like two different animals. I’m going there again soon and am looking forward to that (amoung other things of course).

And on Hog and Rocks, I may be in San Fran soon, I am so glad that I read this entry and saw that link, I’ve gotta go to this place!

I grew up on country ham. My Dad loved it. The best ham I ever had was from the Trigg County Trading Post in Kentucky. One Christmas in the late Fifties he ordered a ham for every agent, all thirty of them, in his agency.

Occasionally he would cook one whole (slow simmered in just barely bubbling water all day and then baked for a little while) but mostly we had it sliced and fried for breakfast, with quail, scrambled eggs and red eye. When I fry it I sometimes add a little Madeira at the end. Keeps it soft.

I need to check and see if that trading post is till around.

Phil

I believe the chicken was created to make eggs to eat with country ham.

Why are central European and balkan countries excluded from the ham belt?

I just don’t know enough about it! I’d like to know more. Most of the stuff I have heard pertains to brine cures smoked products which don’t qualify under the same basic curing criteria.

Thanks to your piece, I had a nice conversation yesterday with Nancy, “The Ham Lady,” at Newsomshams.com. Ordered some vacuum packed slices.

Couple of things: you can reduce the salt content by simmering the slices in water for a minute or two. Discard the water and then gently saute. Adding a little Madeira and cooking the alcohol away, in addition to softening also counters any overly salty taste.

With regard to your comment about farmers in Virginia allowing their pigs to forage in the woods, I read somewhere years ago that Virginia hams got their reputation because the farmers let their pigs forage on chestnuts, which apparently accounted for their flavor. The Chestnut blight ended that.

Thanks again.

Phil

My impression was that they used to forage on the leftover nuts and greens from peanut fields. When peanuts stopped being a major commercial crop in VA the practice died out. People raising hogs on their own property they could let them forage on chestnuts, hickory nuts, or whatever.

Regarding the foraging pigs in the mountainous parts of Virginia, the piece I read said that the farmers actually turned their pigs loose in the woods to forage on chestnuts. Let them run wild and later, presumably after the frosts, called them in to process them. I assume they came when called.

Question: if the ham is vacuumed packed, is it necessary to refrigerate it? The “country” ham you see in the grocery stores are usually, in my experience, is not under refrigeration.

Howdy PhilH,

Uncut country ham does not need to be refrigerated (that’s the whole reason country ham exists!). According to the USDA, certain strains of staph bacteria can survive on the cut face of country hams –so they should be refrigerated. On a personal note –I don’t ever refrigerate hams, but I’m usually eating hams a lot older and drier than the minimum requirements the regulations stipulate for a country ham. I think (but haven’t proven) that staph would have a really tough time surviving on the type of ham I favor.

I ate this ham last week and I’m hooked. The sliced American country ham had a sexy, funky, bbq-ish aftertaste (that’s right I said sexy).

I think its even tastier than most of the Prosciutto San Daniele I’ve consumed. Have you considered hosting a blind ham taste test a la 1976 Paris Wine Tasting? If so, I’m in!

I have done tastings before –but not blind. The problem is, the American hams are easy to pick out cause the salt lever is higher and they have that funky taste. I usually prefer the Americans, but it depend on my mood and the application.

i have been buying, eating hams from the family widely regarded as kentucky’s #1 purveyor for 25 years. my fanaticism for these hams is unbounded. (i have traveled from my home in nyc to kentucky to visit the supplier, who i now consider a friend.) my problem: in recent years the majority are partially or wholly spoiled, despite what appears to be good and proper care throughout the aging process. (i simmer the hams, skin them and glaze/bake.) i can only surmise that the cure is not proper. i prepare and eat two hams a year, and of the last 7 only one or two were uniformly of the quality expected. (i age the hams from six months to a year after delivery, in clean, bug-free settings.) why is this happening? can i do anything about it? is it possible that the nyc environment introduces problems or is it more likely that the problems occur in the curing process, as i suspect. very frustrating and looking for any insights, perspective….

Interesting problem. I have had hams that were spoiled (usually near the bone). I assume due to improper curing. I usually cut away the bad parts –the taint– and use the rest. That might be harder with a cooked ham. If you bone out the hams before you cook them you’ll catch the problem and be able to salvage more. A friend of mine says this fault has been on the rise recently. His theory is that it happens when companies increase their production to meet rising demand and they make errors. Most producers salt down the hams in big piles that are periodically overhauled during the curing process. My guess is that the error are being made at that point in the process.

NB: I used to age hams in my apt. Watch out for mites. Once I got a ham that had mites, then all my hams had mites. Drat. I also once had a beetle problem –the little suckers bored into the ham right above the fat line on the face of the ham. The next time I’m smearing the whole thing with lard.

We keep a leg of Seranno behind the bar at work, where we slice it to order with knives, rather than a machine. Pain in the backside in the middle of service, but it’s a really nice touch; we get a lot of customers who’ll sit at the bar with a good glass of red wine and order up a small plate of the ham, which we’ll serve up with some olives and Manchego cheese. It’s a great little continental touch.

I got together with a friend of mine recently for a bit of a treat – we ordered some pate negra, Eduardo Sousa foie gras and I brought along a bottle of Jurancon Doux (a sweet wine from the south-west of France). Possibly one of the best picnics ever.

Hi Ruari,

I have always wanted to do a side by side tasting of the same ham hand sliced versus machine. They are undoubtedly different. I wonder what the majority of people would prefer? Hand cutting makes for a sexier service though.

my question appears to have disappeared

What question Stoneburn? I’ll try to get it back.

couldn’t find an email address for you guys so i thought this would be as good a place to post this question as any. what gives with all the newer organic products that list nitrite and nitrate free? i understand that a few people are using celery juice but to my understanding it still contains nitrates. is the statement of no nitrites simply a matter of USDA rules or is there something else going on here? Also any posts or insight into using celery juice would be interesting.

Hi Matt,

I think the nitrite/celery juice is just another example of J.Q. Public getting snowed by a clever workaround to USDA rules. I personally have no problem with nitrates –they prevent botulism, produce a nice rosy color, and produce that characteristic cured taste we all love. There are people who want the cured taste but don’t want nitrates/nitrites on the ingredient statements (Whole Foods, for example). They locate a food that contains a relatively high concentration of nitrates/nitrites that can be concentrated (celery) without providing too much off-taste to the product –Voila! Nitrite Free (at least as far as the ingredient list goes).

A similar example is products that are “free of MSG.” I was at a food show where a salesperson handed me a cup of dashi made with kombu and katsuo-bushi. She exclaimed that the soup was “free of MSG.” I nearly hit the ground laughing. After all, MSG was originally isolated from kombu as a result of tasting kombu-dashi!

I clearly have never had a good American ham. Thanks for the post, I am now on the hunt.

My best friend of 18 years and her family are from Spain. They order a Burgers Smokehouse attic aged ham each year. It is so amazing, each time I eat it I go on mad hunt for a “jamon serrano”. I ordered an attic ham a few years back and was completely baffled when the directions stated, cook it. I followed my friends method, placed it in my ham stand that they brought me from Spain and left it on the counter to slice. I figure they do it each year, no one ever gets sick, it must be fine…however, it was too much ham, no one else in my family was willing to eat “uncooked” ham and therefore most of it went to waste and just got too dry to cut. But every month I start to salivate just thinking about it, so I think after the holiday money craziness I am going to invest in myself and get a ham Thank you for your article I definitely will feel safer with my next ham.

Thank you for your article I definitely will feel safer with my next ham.

I have just been gifted a 13.5 pound hickory-smoked country ham from Johnston County Hams. Should I be ecstatic?

Also, what’s the best way to slice these bone-in hams for eating raw?

Howdy Slkinsey,

Johnston County Hams are made in Smithfield North Carolina (if my memory serves me right) and are sometimes marketed as Smithfield hams, which I find hilarious. I don’t know anymore, but the last time I checked their cure master was Rufus Brown (I think). Rufus was a master at getting hams to age relatively quickly without case-hardening. He’d get a ham as dry as a normal 9 monther in about 4-5 months. I’m not going to say anything negative about his ham –it tastes good (way better than an actual Smithfield), but not as good as if it had been aged longer. You can accelerate drying, you can even accelerate aging somewhat by manipulating temperatures, but you can’t truly fake age. The other problem with the fast aged hams is they tend to be more difficult to slice raw and the slices don’t stay in top condition as long (I don’t know why).

That said, I have eaten plenty of Johnston county ham raw. I would cut off the aitch bone with a meat (or hack, or better yet band) saw, then cut off the hock side at the knuckle and carve out the bone in the cushion. That’ll let you cut the ham on a meat slicer. Otherwise you can trim off the skin in the area you are going to slice, put the bone-side down on the table in a clamp and make horizontal slices through the cushion of the ham with a slicing-knife Spanish-style.

Tell me how it goes.

oooooh what an amazing gift. Get a ham stand and spanish knife.

Hi Dave,

Loving this site and podcasts!! I am cooking in China, and my buddy and I have had some pretty big pork legs (around 11kg/pc), and they have been brining for about 18 days which is the right amount of time from our calculations. We are now thinking of low temperature cooking these bad boys for “insurance” from spoilage or anything nasty. Could you give me an internal temperature plus maybe guide to temperature and times for achieving this!

Howdy Hamish,

Did you use nitrites? If you did, 60C is a great temperature for ham. How long it cooks depends on the thickness of the ham. This is one case where I’d actually use a thermometer. Pull it after it gets to 60 at the core (I’d let it ride a little longer just in case).

Thanks Dave, yep we did use nitrites in a “Wiltshire” inspired brine! We are also toying with the idea of cooking the ham’s in cider…will aim for 60 then!

Dave, can you send me some info on the humidity and temp. that the different styles (American vs. European) of curing experience? I have been doing some curing, and I just put together a curing box, and am working on temp. and humidity control. Right now I’m working on fermented style sausage like soppressata and dry cured braseola, but plan to age some small heritage breed hams soon .

I don’t have the info on me Jonathan, but the author to look at is Fidel Toldra. His old book (the only one I have of his) is called Dry Cured Meat Products. I think he has a new book. His old numbers on American hams are a little strange if my memory serves me, but Sam Edwards saw him speak a while ago and says Dr. Toldra knows what’s up.

I have a question and am hoping you can give me an answer. I received a country ham for a Christmas gift. I was told you can store them almost indefinitely. So I put it in my refrigerator. Now I’m told they should be stored in the cupboard. So my question is, did I ruin it by storing it this way and have I stored it to long? Any answers would be appreciated. Thanks KHP

You didn’t ruin the Ham KatyHP. Depending on how you wrapped it the surface might be tack and need to be trimmed off. Weird surface mold (of the not good kind) might have grown on the outside, etc (I have had all this happen), and aromas from the fridge might have permeated the fat. If the ham is whole, scrub it down to rinse off the surface mold and give it a sniff. If it smells like fridge you’ll need to trim off a bit off the outside (don’t trim too much! just enough to get past the fridge taint). If the ham has been cut already and you have any fridge mold (normal country ham mold is blackish or whitish, fridge mold can be real bloomy white, like brie, or green), trim it off (again don’t go crazy).

Best place to store a ham that you don’t want to age anymore is in the freezer. I used to store mine hanging in the kitchen, which is great, until you get attacked by beetles (which happened to me once) or mites. Mites can go crazy on an unattended ham in a cupboard –take it from me.